The Trolley Problem Is the Most Honest UXR Metaphor and We All Know It

The trolley problem is simple enough: a runaway trolley is barreling down the tracks toward five people who can't escape. You stand next to a lever that can divert the trolley to another track where only one person will die. Pull the lever, kill one. Do nothing, kill five.

Philosophers have debated this ethical dilemma for decades. Utilitarians say pull the lever—one death is better than five. Deontologists argue the moral weight of action versus inaction. The discourse continues in university halls, over wine, in thought experiments.

But in User Experience Research? There's no debate.

You pull the lever. Every. Damn. Time.

You're standing at the lever. Five users are tied to one track. Their feedback is rich, their needs well-documented, their pain points mapped with empathy and stickies and cross-tabs. On the other track is one single, shiny business objective—"maximize engagement," "increase conversion," "reduce churn." Whatever.

The PM looks at you: "Well? What does the research say?"

You pull the lever. The users die.

🚋 The Lever Always Gets Pulled 🚋

Welcome to user experience research.

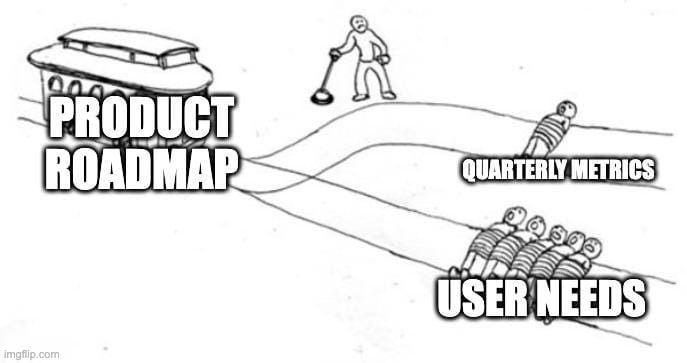

The trolley problem isn't some philosophical curiosity in UXR. It's Tuesday. Except the lever is product roadmap prioritization. The users are segments. And the person pulling the lever is usually you—or worse, you're told you're pulling it, when actually it's already been wired into the backend OKRs.

"Oh, we're cutting support for older devices." "Oh, dark patterns tested better with 18-24s." "Oh, the edge cases you're worried about represent less than 5% of MAUs."

Translation: "We're going to let five people die. But it's okay because they're not the right five people."

Metrics have become the morality of product teams. Not qualitative insight. Not deep, conflicted understanding of real human messiness. No, it's always:

"What's the bounce rate?" "What's the uplift?" "Can we A/B test that before you go all Kant on us?"

In the world of UXR, pulling the lever is just conversion optimization with extra guilt.

And don't you dare bring up the one person on the other track—the one you could've saved, the edge case, the vulnerable user. You'll get that look: "We have to scale."

Sure. Scale the trolley.

We host user panels. We make frameworks. We give talks. We wear "Users First" t-shirts. But when the moment comes—when the PM is breathing down your neck, the deadline is in two days, and your report says something inconvenient—you pull the lever. Or someone pulls it for you, and you document the impact post-mortem in a debrief no one reads.

Let's not lie to ourselves: UXR is often less about "doing what's right for users" and more about making it look like we tried.

You write reports no one opens. You quote users who begged you not to ship it like this, only to watch it go live exactly like this. You write recommendations that get watered down, reworded, re-scoped, and eventually filed under "nice to have." You do evaluative research on a feature that's already two sprints deep into development. You present clear, sharp risk that gets minimized, reframed, or dismissed because "that's just qualitative." Then you get pinged three weeks later when the metrics tank and someone says, "Could we have predicted this?" You did. It's in the deck. Slide 9.

Once something becomes a KPI, it stops being a number and becomes a sacred object. You can't question it. You can only align with it. And if chasing it steamrolls actual humans—well, that's just optimization.

🧠 Sage Advice on How to Navigate This 🧠

So here's the advice for researchers who are tired, bitter, and still showing up:

Treat research like a heist. Get in, steal truth from chaos, and slip it into the roadmap disguised as strategy. Don't say "this will hurt users"—say "this will increase churn in our high-LTV segment." Make pain sound expensive.

Speak their language, not yours. No one cares about "cognitive load" or "mental models." They care about conversion, retention, and whatever buzzword the CEO dropped in the last all-hands. Translate user suffering into business metrics. It's not "confusing"—it's "creating a 22% drop-off at verification step." It's amazing how quickly empathy appears when you put a dollar sign in front of it.

In UXR Survival Guide: One Giant Duck, 1000 Tiny Horses, and Organizational Maturity, I broke down essentials like the “Evidence Arsenal,” “Trojan Horse,” and “Research Theater.” But in the high-stakes, lever-yanking world of the Trolley Problem, we need a few new plays—darker, sharper, more subversive. These aren’t just survival strategies—they’re acts of quiet rebellion.

Don't ask for buy-in—build alliances. Make yourself impossible to ignore. Work with design. Befriend support—they're drowning in the tickets from your last ignored research. Cultivate spies in customer success who will forward you the angry emails that never make it to the product team. Make the engineers like you—they're the ones who can secretly add accessibility fixes as "tech debt" when no one's looking. Create your own UXR resistance movement—guerrilla researchers operating behind enemy lines, sharing intelligence over slack coffees and discreet emoji reactions.

Get PMs to trust you just enough that they don't want to argue with you in front of stakeholders. Be feared, not loved. Be the person whose slide deck makes people shift uncomfortably in their seats. Perfect the art of the well-timed "Actually..." that derails groupthink without making you sound like a jerk. Become the research equivalent of that one person in horror movies who keeps saying 'I don't think we should go in there' before everyone gets murdered.

Package your findings like ammunition, not insight. Leaders don't want knowledge—they want weapons to win arguments they're already having. Figure out which battle they're fighting and hand them exactly the right bullet. Research becomes currency in the corporate game of thrones. Distribute it strategically to the players most likely to actually do something with it.

When all else fails, master "The Sacrifice Play." Deliberately offer up minor features or ideas as sacrificial lambs in review meetings. These decoys are designed to get shot down while protecting more important user needs. "I think we should consider auto-playing music on the landing page" becomes the feature everyone gleefully rejects while your actual priority—fixing that critical accessibility issue—quietly slides through approval. Stakeholders feel smart for catching the "bad idea" while missing that you've redirected the trolley away from your most vulnerable users.

Perfect "The Empathy Time Bomb" technique. Plant emotionally powerful user quotes or videos in presentations, carefully timed to detonate at precisely the right moment in decision-making processes. These aren't just findings—they're delayed-action reality checks. Casually mention, "Before we finalize, let me just share what User 12 said..." and then play the clip of a frustrated customer that perfectly captures the problem everyone's been trying to ignore. The key is timing—save these bombs for when the decision is almost made but still reversible. Let them sit with the discomfort just long enough to change course.

Perfect the "Yes, And" technique with executive shower thoughts. When the CEO announces their latest epiphany at 4:59 PM on Friday—"What if our accounting software was more like Snapchat?"—don't oppose directly. Instead, channel your inner improv performer: "Yes, ephemeral features could be interesting, AND before we commit, let's understand how our users might respond." This acknowledges the idea while redirecting enthusiasm toward proper validation, like herding a caffeinated toddler away from a knife display.

Keep your receipts—not out of pettiness, but principle. Document everything. Record meetings if you can. Save Slack threads. Screenshot decisions. Because when the trolley hits, someone will say "no one could've seen this coming," and you will know otherwise. And you'll need proof when the postmortem happens and collective amnesia sets in. Your career may depend on your ability to politely say "Actually, we discussed this exact scenario on March 12th" while pulling up the receipts.

Grow a very thick skin. You'll be invited to the table, then ignored at the table, then blamed for what happened at the table. Don't take it personally—it's just how the trolley turns. Your job is to represent users in a room where users aren't welcome.

Learn to laugh. Laugh at the A/B tests that proved nothing. Laugh at the feedback surveys that no one read. Laugh at the term "Minimum Lovable Product." Laugh when they roll out a feature users begged you not to ship, then panic when users hate it exactly as predicted. You're not broken if you're bitter. You're just awake. Cynicism isn't a character flaw in UXR—it's an evolutionary adaptation.

Find your tribe. There are other researchers out there, pulling their own levers, documenting their own casualties. Trade war stories. Share templates. Warn each other about organizations where the trolley never stops. Create a shadow network of fellow researchers who understand that the corporate UXR landscape makes about as much sense as fighting one horse-sized duck.

🚋 Sometimes, You Do Stop the Trolley 🚋

And sometimes—sometimes—you do stop the trolley. You buy time. You delay launch. You change a headline. You save a user segment. You say something in a meeting that actually lands. You see a roadmap get slightly less terrible because of something you said four weeks ago in passing. That's the job. Not winning. Not fixing everything. Just pulling as hard as you can on a lever that mostly doesn't move.

And remember this: If you're in UXR and you feel like your job is standing at a lever that's already rusted into position, you're not alone. And if you still fight to yank it the other way—even when you know it won't budge—that's not failure.

That's the job.

Sometimes, we do stop the trolley. Sometimes, research saves a feature, re-centers a roadmap, or prevents real harm. But most days? Most days we're building elegant cases for choosing which track to send the trolley down, and hoping nobody notices the bodies.

🎯 Still here?

If you’ve made it this far, you probably care about users, research, and not losing your mind.

I write one longform UX essay a week — equal parts strategy, sarcasm, and survival manual.

Subscribe to get it in your inbox. No spam. No sales funnels. No inspirational LinkedIn quotes. Just real talk from the trenches.

👉 Subscribe now — before you forget or get pulled into another 87-comment Slack thread about button copy.